Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...- Home

- Bookstore Blog

- Archimandrite Vladimir: A Personal Remembrance

Archimandrite Vladimir: A Personal Remembrance

Posted by John Martin on 28th Jul 2015

Note: Today, the feast of St. Vladimir of Kiev, is also the nameday of Archimandrite Vladimir (Sukhobok), who used to run the monastery bookstore. Fr. Vladimir reposed in 1988. The following is a personal remembrance of Fr. Vladimir by Joseph McLellan (later Archimandrite Joasaph, †2009), who graduated from Holy Trinity Seminary in 1985. It is republished with permission from Orthodox America, Vol. IX, No. 6 (January 1989).

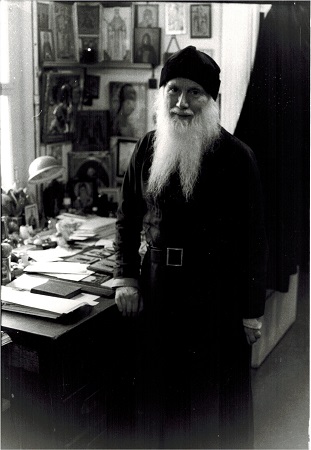

In the course of our lives we are sometimes privileged to meet people who bear witness to God’s power to transfigure sinful human nature and to make out of ordinary men extraordinary vessels of His grace. Such a person was Archimandrite Vladimir of Holy Trinity Monastery. It was only fitting that he departed this life the day after the Feast of Transfiguration. Archpriest Valery Lukianov, in his eloquent tribute to Fr. Vladimir, described him as the monastery’s “little sun.” Indeed, he radiated such kindness as to warm the hearts of those fortunate to have contact with him. And there were many. A great crowd of people from all over North America packed the monastery church for his funeral—in spite of it being a weekday. He was a rare person altogether, and it would seem that no words could do justice to his memory. But for those who never met him, even a second-hand acquaintance, provided in the personal glimpses which follow, can perhaps serve to edify and inspire.

Pilgrims to Holy Trinity Monastery will remember Fr. Vladimir from the office and the bookstore which he oversaw for the last 21 years of his life. Upon meeting him for the first time one could not but be struck by his appearance: he was short, little more than five feet tall, and had a long, snow white beard. Even more striking was his seemingly inexhaustible energy. His speech, his movements—all were brisk and precise. And he was always animated and cheerful. Even though the office was a place where money changed hands, an administrative center where people came on business, it felt like a holy place because Fr. Vladimir made it a place of prayer. Before leaving the monastery, pilgrims would often come to Fr. Vladimir for a blessing; he would sometimes serve a short moleben for them, and always blessed them with a cross from the Holy Land and anointed them with holy oil, usually from the tomb of the Mother of God.

I met Fr. Vladimir on my first visit to the monastery 13 years ago. On that occasion he gave me my first prayer book in Church Slavonic. Later as I came to visit the monastery for longer periods and eventually entered the seminary, I learned that such generosity was characteristic of him, even legendary. He used to give away so many books and icons that I wondered how the bookstore could ever show a profit. Often the “price” for something would be a candle lit before the icon of St. Seraphim of Sarov, next to the monastery’s main church. Fr. Vladimir had great veneration for St. Seraphim, and it seems to me now that his “business” practice was based on St. Seraphim’s advice; he exhorted people to be “wise merchants” by using their abilities on earth to store up treasures for themselves in heaven. Fr. Vladimir did just this, using the resources available to him to do as much good as possible for others. Like the sower in the Gospel parable, he spread spiritual literature and holy icons far and wide, often without any material compensation.

Like St. Seraphim, Fr. Vladimir had a special love for the Mother of God. He was never happier than when the Kursk-Root Icon of the Mother of God visited the monastery—the very Icon before which St. Seraphim was healed as a child. At those times he would be busy serving molebens and akathists, and arranging for the Icon to visit people’s homes and monks’ and seminarians’ cells. Often he would keep the Icon in his own cell overnight and pray before it: When the Iveron Icon of the Mother of God began to stream myrrh, he saw it as a reminder of her mercy to the world, and sent paper reproductions of the Icon together with cotton soaked in the myrrh to many of the people who wrote to him, usually accompanied by a short note describing the miracle and a reminder to pray to the Queen of Heaven.

I have known two people who showed as strong belief as Fr. Vladimir in the power of prayer. You could never get advice from him that did not include instructions to pray. He himself put this advice into practice on every possible occasion. After compline, many people would go downstairs to venerate the icons in the lower church where, more often than not, they would find Fr. Vladimir serving a panikhida. He took upon himself the responsibility of keeping the lists for commemoration up to date, and he constantly remembered the living and the dead in prayer, both in molebens and panikhidas and during Proskomedia. At one point a group of seminarians started singing the akathist to the Mother of God every Friday night in church after compline. When Fr. Vladimir learned about this, he began regularly serving the akathist for them

That was another characteristic trait: Fr. Vladimir was always anxious to encourage people’s good intentions. You might say he invested in people. If he saw that someone had talent as an iconographer, for example, he often encouraged them by commissioning them to paint for orders the office had received. He was also a great supporter of the seminary choir, knowing that it gave the seminarians an opportunity to do something enjoyable while beautifying the services.

Individual cases of his generosity are too numerous for human reckoning. Large sums of money passed through his hands from those requesting his prayers to those in need of help. To give an example from my own experience, I needed a large sum of money in order to graduate. I had most of it in a savings account and my parents were willing to give me the rest, but there was no way I could get it all together in time to avoid an unpleasant consequence. In the office one day I approached Fr. Vladimir for a blessing. Sensing I was in difficulty, he led me to a quieter place and asked what the problem was. “I see. That’s a lot of money. Well, I can give it to you if you want, and you can pay me back when you’re able.” I somehow managed to stammer out my thanks, but he was all business. “Meet me here in an hour, and I’ll have it ready.” When he gave it to me, I said something to the effect that I didn’t know how to thank him. He said, “It’s all right; this way you’ll graduate, and you’ll pray...” He was a wise merchant.

Fr. Vladimir loved birds and was always feeding them. You couldn’t step into the office’s main storeroom without tripping over one of Fr. Vladimir’s 25-pound bags of birdseed. At night he could often be found in the refectory, cutting dried bread crusts into small pieces for his birds. Probably as a result of this, the monastery was a regular stopping place for many different kinds of migrating birds, some of whom I had never seen before in the Northeast. In fact, the only time I ever recall seeing Fr. Vladimir angry was when cats frightened away some birds

Fr. Vladimir had a gift for teaching: he taught 3rd- and 4th-year Church History at the seminary. Instead of presenting us with dry outlines of events, he tried to inspire us with the lives and labors of the holy men and women, the “principals” in Church history, beginning with the holy Apostles. His own life was an inspiring example. It is always possible, after all, to read about Christianity in books, but in Fr. Vladimir we had before us a living icon of what the goal of our life in Christ, in the Church should be. And that was the best lesson of all.

Fr. Vladimir also had unimpeachable moral authority, both within the monastery community and outside. Although he did not hear confessions, he had keen discernment and many people turned to him for advice. A fellow seminarian once pointed out to me that while other people could chastise you at length and have no effect, all Fr. Vladimir had to do was say one word, and you would instantly be overcome with a feeling of repentance. Likewise, when we had an idea for a project, we would use Fr. Vladimir’s opinion as a test to see if the idea was worthwhile. If he approved, we would go to Archbishop Laurus for his blessing. If, on the other hand, Fr, Vladimir didn’t like the idea it usually meant it wasn’t worth bothering the Rector about it.

Because of the kindness and hospitality he showed to visitors, as well as his reputation as a man of prayer and spiritual discernment, Fr. Vladimir received mail from people all over the world who wrote to him with their troubles and sorrows. Keeping up with this correspondence was probably a greater burden than most of us realized. It was at night, after the rest of the monastery had gone to bed, that he read and answered his mail. Those who worked with him often came into the office to find him somberly reading a letter, occasionally sighing and crossing himself, suffering with the person who had written him. He frequently served panikhidas and molebens right there in the office in answer to the many requests he received for prayer.

Fr. Vladimir loved children, and it was always touching to watch him around them, because they obviously loved him in return. This was certainly true of my younger sister and brother, even though they did not speak Russian and Fr. Vladimir’s English was limited although he understood it very well. It seemed to me that he would have made a wonderful father, in fact, in the course of his monastic life, he had become precisely that: a father in Christ to generations of younger monks and seminarians, clergy and lay people all over the world. I believe that it was about people like Fr. Vladimir that the Apostle Paul wrote: For though ye have ten thousand instructors in Christ, yet have ye not many fathers.

Fr. Vladimir spent nearly forty years in the monastic life, which was for him a great happiness, although he bore his share of suffering, both spiritual and physical. In the last months of his life he endured a painful brain tumor. Now, however, he has gone there where there is neither sickness, nor sorrow, nor sighing. And just as he sowed an abundance of goodness in his life, so shall he reap the reward of his labors. May his memory among us be eternal.

Joseph McLellan