Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...- Home

- Bookstore Blog

- liturgics

Bookstore Blog - liturgics

Russian Orthodox Funereal Practices

Posted by John Martin on 15th Jul 2015

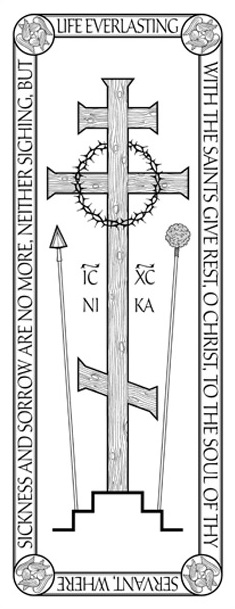

“Pale death watches over us all.”

—Derzhavin

From time immemorial, people have been burying their dead with ceremony and prayer. The Holy Orthodox Church has a number of prayer services for the dead, beginning with the departure of the soul from the body, through the funeral service itself and afterwards. These services serve both to assuage the mourning, who are given a hope of the future resurrection, and to succor the souls of the departed, so that they may be granted eternal rest in a place “whence all sickness, sorrow and sighing have fled away.”

From time immemorial, people have been burying their dead with ceremony and prayer. The Holy Orthodox Church has a number of prayer services for the dead, beginning with the departure of the soul from the body, through the funeral service itself and afterwards. These services serve both to assuage the mourning, who are given a hope of the future resurrection, and to succor the souls of the departed, so that they may be granted eternal rest in a place “whence all sickness, sorrow and sighing have fled away.”

In addition to prayers, there are also a number of folk customs which developed in Orthodox countries. Some of them are superstitious, such as throwing out all the water in the house so that the departed soul would not become “stuck” in them. Other customs are natural outgrowths of traditional piety. This post describes the funereal prayer services and customs of Orthodox Russia.

The First Days after Death

Just before death, an Orthodox priest says one of several canons “At the Departure of the Soul” (found in the third volume of the Great Book of Needs). He prays that the dying person may “escape the hordes of bodiless barbarians,” i.e. the demons who desire to pull the departed soul into Hades, and to instead “rise through the aerial depths and enter into Heaven.”

After the repose, the priest says (at the home, hospital, or wherever the death has occurred) the so-called First Panikhida, the “Office at the Departure of the Soul from the Body.” Calling to mind Christ’s descent into Hades and His Resurrection, the priest prays for the newly-reposed servant of God, that he may be granted “rest in the bosom of Abraham.”

Laymen, priests, and monastics are prepared in different ways. The body of a layperson is fully washed and clothed, and a burial shroud is placed over him or her. Formerly, the bodies of the departed in Orthodox Russia lay on the dining room table for three days after their repose, positioned so their heads were underneath the icon corner. The great Russian poet and statesman Gavrila Derzhavin (1743-1816) poignantly describes this custom in his “On the Death of Prince Meshchersky”:

|

Утехи, радость и любовь

Где купно с здравием блистали, У всех там цепенеет кровь И дух мятется от печали. Где стол был яств, там гроб стоит; Где пиршеств раздавались лики, Надгробные там воют клики, И бледна смерть на всех глядит. |

Where once amusement, joy, and love

Shined all together with good health, Now there the blood is freezing in our veins, Our souls are plagued by grief. Where once a feast was spread a coffin lies, The place where festive singing rang Now hears but graveside keening, And pale death watches over all. |

Until the funeral, the Psalter is read over the body of a layman, but for a departed priest the Gospel is read. At Holy Trinity Monastery, the monks and seminarians continually read the Psalter in one-hour shifts in both Church Slavonic and English. While reading, it is customary to say special prayers for the departed after each section ( kathisma) and sub-section (stasis) of the Psalter. These prayers are contained in A Psalter for Prayer.

The Funeral Service for the Laity

For the funeral, the deceased layperson is dressed in regular clothes, with a

burial shroud folded on top of the body; at the end of the funeral the priest will cover the body with the shroud. Over the forehead is a headband made of paper or cloth with the words “Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us.” A cross is usually placed in the hand of the departed.

For the funeral, the deceased layperson is dressed in regular clothes, with a

burial shroud folded on top of the body; at the end of the funeral the priest will cover the body with the shroud. Over the forehead is a headband made of paper or cloth with the words “Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us.” A cross is usually placed in the hand of the departed.

The Funeral Service for the laity mainly comprises Psalm 118 (sung in three parts with refrains), a canon for the departed, readings from Scripture, and various hymns. After the reading of the Gospel, the priest reads a prayer of absolution and then places it in the hand of the departed. Then, while the choir is singing funereal hymns, the loved ones of the departed come up, make prostrations, and kiss the cross and the headband. The priest, after covering the body with the burial shroud, sprinkles in some dirt and holy oil, and closes the coffin. If there is no cross inscribed on the coffin, the priest will often drip candle wax on the head of the coffin to make a cross.

The coffin is then placed in a hearse and driven to a cemetery for burial. While carrying the coffin, it is customary to sing “Holy God…” At Holy Trinity Monastery, the cemetery is just up the hill, and the coffin is accompanied by a cross procession, with the chanters slowly singing “Holy God…” At the cemetery there is another short burial service, at the end of which everyone participates in burying the dead by throwing in a handful of dirt. In former times at the monastery, shovels used to be handed out to a few people and the burial done then and there.

After the burial it is customary for there to be a memorial meal (pominki) in honor of the deceased. Although at the monastery this usually means richer fare such as fried fish, in Old Russia there were several traditional foods prescribed for eating at a memorial meal, such as bliny (Russian crepes) and kutya (pudding with boiled wheat berries). According to the life of Blessed Xenia of St. Petersburg, the holy fool-for-Christ once went about knocking on windows, saying “Save up flour; we will bake pancakes.” Two days later, Empress Catherine II reposed, and soon all of Russia was making bliny. Kutya is made with wheat berries mixed with honey and nuts, and with some minor differences is identical with koliva made in Greece and the Balkans. The wheat berries used in these traditional dishes calls to mind the saying of Christ, predicting His death and resurrection: “Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit (John 12:24).” In addition to these foods, the faithful also give out sweets, asking for prayers for the souls of their loved ones.

After the burial it is customary for there to be a memorial meal (pominki) in honor of the deceased. Although at the monastery this usually means richer fare such as fried fish, in Old Russia there were several traditional foods prescribed for eating at a memorial meal, such as bliny (Russian crepes) and kutya (pudding with boiled wheat berries). According to the life of Blessed Xenia of St. Petersburg, the holy fool-for-Christ once went about knocking on windows, saying “Save up flour; we will bake pancakes.” Two days later, Empress Catherine II reposed, and soon all of Russia was making bliny. Kutya is made with wheat berries mixed with honey and nuts, and with some minor differences is identical with koliva made in Greece and the Balkans. The wheat berries used in these traditional dishes calls to mind the saying of Christ, predicting His death and resurrection: “Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit (John 12:24).” In addition to these foods, the faithful also give out sweets, asking for prayers for the souls of their loved ones.

Memorial meals usually take place at the church hall or trapeza, but oftentimes people still follow the old custom of actually eating at the cemetery. In the above photograph, taken in 1919, we see a family eating practically over the grave of their departed relative!

The memory of the dead does not end with the funeral. Indeed, we pray that the memory of the departed may be eternal. According to custom, panikhidas are served on the first, third, ninth, and fortieth days after death, as well as on the Name Day of the reposed and the anniversaries of his or her death.

In the modern world, people often avoid thinking about death. Modern funeral services are sterile affairs, and death is rarely discussed openly. However, the customs of the Orthodox Church banish the fear of death. Death is not something to be feared; rather, for the Orthodox Christian, death becomes a portal to eternal life.

The History and Meaning of Incense

For from the rising of the sun even unto the going down of the same My name shall be great among the Gentiles; and in every place incense shall be offered unto My name, and a pure offering: for My name shall be great among the heathen, saith the Lord of hosts.” (Malachi 1:11) The liturgical services [...]

Creating a Liturgical Library

The Divine services constitute a treasury of theology and life for all Orthodox Christians. Whilst compiled and formed throughout the ages by men, they were guided by the Holy Spirit, who guides the Church into all truth (cf. John 16:13). Therefore, we do not just believe the divine services are interesting sources of theology, or men's expressions of worship – they [...]